The bottom line seems to always be salvation - is a person 'saved'. We are obsessed with this question to the distortion of the gospel, the church, the kingdom, and spirituality. We look at the world in terms of who's in and who's out. We create an exclusive mindset foreign to God as displayed in Jesus.

I suggest a new question that will help us see the world correctly: 'is this person loved?'

Now everyone is 'in' and I ought to treat them as such. Everyone is loved, and I am to help everyone discover how to live in that divine love by discipling them. When Jesus was seeking and saving the lost was he looking for outsiders to bring on the inside, or was he seeking and redirecting those who'd wandered away from God - but who were still God's children?

Our sinful actions make us enemies and aliens to God, but God is no alien and enemy to us. He is always the loving Father, close and caring. The prodigal stopped being a son to his father, but the father never stopped being father to the boy.

From the son's perspective, he was on the 'outs' with his father, but such was not the case from the father's perspective. His son was always 'in' even though the older brother never understood it. The lesson isn't just for the older son to acknowledge the return of the younger, but to develop the kind of love the father always had for the prodigal. The father's love for the prodigal never saw him as having lost his place in the family, just his way of living in harmony as part of the family. We are the superior-feeling older brother when we banish the prodigal from the family because he's foolishly lost his way.

We do no wrong if we consider all the world 'in' by virtue of God's love. Not only are we not approving of sin, we find ourselves in a better posture by virtue of love and acceptance from which to make disciples of all nations.

Thursday, February 24, 2005

Tuesday, February 22, 2005

The Horse Whisperer

I watched the Robert Redford movie The Horse Whisperer last night. It is the story of a mother who takes her daughter and the daughter's horse, both injured in an accident and bearing physical and spiritual scars, to a Montana cowboy renowned for his ability to communicate with horses. It is soon obvious that the "uninjured" mother is just as scarred as her daughter and the horse.

As I watched the story unfold the thought kept coming back to me that Robert Redford's character, Tom Booker, the gentle cowboy who can heal horses, is a spiritual director. His way with the horse, the daughter, and the mother serves as an example of what being a mentor, a sage who nurtures spiritual formation, is really about.

Tom listens and tries to understand first. He doesn't start with answers - but with questions. He is extremely patient, not claiming to know when or how the needed changes will take place. He admits his limitations, but points back consistently to what is true and real - even when those are painful realities most would rather avoid.

He is deliberate in pointing out to each the personal responsibility inherent in embracing inner change. His "techniques" are like spiritual disciplines, tailored to create the setting for personal decision and change. Significantly, he contradicts the language of denial - especially when the mother wants to pretend that she can't do anything about her failing marriage. Tom makes it clear that she has a choice to return home to her husband and work on their relationship - that transformation is possible.

When the mother says she has to keep trying to fix things, although it never seems to work, Tom asks why she can't just let things fail. She says she can't, and he asks again, why not? To that she has no answer.

The character of Tom is someone with clear self-understanding, and who knows who he is and where he belongs in life. There is a kind of peace he has which others want, but which requires a type of sacrifice and journey they may not want to take.

All this isn't to say that the film is without some flaws - a notable one for me is that the rural community that Tom is part of is idealized and serene - as if that rustic Montana community is composed entirely of spiritually mature people at peace with themselves, their neighbors, and the environment. That romantic contrast between rural and urban life is not realistic.

But still, I think the Tom Booker character serves as a good archetype for a spiritual mentor . . . and gives us a useful image of how spiritual maturity can be expressed in ordinary daily circumstances.

As I watched the story unfold the thought kept coming back to me that Robert Redford's character, Tom Booker, the gentle cowboy who can heal horses, is a spiritual director. His way with the horse, the daughter, and the mother serves as an example of what being a mentor, a sage who nurtures spiritual formation, is really about.

Tom listens and tries to understand first. He doesn't start with answers - but with questions. He is extremely patient, not claiming to know when or how the needed changes will take place. He admits his limitations, but points back consistently to what is true and real - even when those are painful realities most would rather avoid.

He is deliberate in pointing out to each the personal responsibility inherent in embracing inner change. His "techniques" are like spiritual disciplines, tailored to create the setting for personal decision and change. Significantly, he contradicts the language of denial - especially when the mother wants to pretend that she can't do anything about her failing marriage. Tom makes it clear that she has a choice to return home to her husband and work on their relationship - that transformation is possible.

When the mother says she has to keep trying to fix things, although it never seems to work, Tom asks why she can't just let things fail. She says she can't, and he asks again, why not? To that she has no answer.

The character of Tom is someone with clear self-understanding, and who knows who he is and where he belongs in life. There is a kind of peace he has which others want, but which requires a type of sacrifice and journey they may not want to take.

All this isn't to say that the film is without some flaws - a notable one for me is that the rural community that Tom is part of is idealized and serene - as if that rustic Montana community is composed entirely of spiritually mature people at peace with themselves, their neighbors, and the environment. That romantic contrast between rural and urban life is not realistic.

But still, I think the Tom Booker character serves as a good archetype for a spiritual mentor . . . and gives us a useful image of how spiritual maturity can be expressed in ordinary daily circumstances.

Monday, February 21, 2005

Spiritual Formation and the Arts

The heart, the inner spirit and will of a person, is the most inaccessible part of a person to try and form. The mind can be spoken to directly, the body can be dealt with tangibly . . . but the heart seems the hardest to reach.

Since the heart is connected in one person to the mind and body, there is an indirect route through those parts. Discourse that immediately engages the thinking of a person may have a deeper resonance into the heart. The actions of the body which can be disciplined may have repercussions to the spirit. But the hardest part to reach, is the most important to be shaped.

We know that out of the heart a person speaks, meaning that both the thoughts of the mind and actions of the body are directed by a person's spirit. Emotions too are reflections of one's heart. The essence of spiritual formation is focused on the transformation of the human spirit by God's Spirit -with consequences for every other part of a human being.

I wonder if the arts are a way of speaking more directly to the heart. Moving music, an engaging story, a well-directed film, evocative paintings, poetry, and many other 'arts' seem in my experience to get into a person's heart, or spirit . . . pushing beyond the mind's thoughts and body's actions.

Not every use of the arts speaks to every person's spirit, but I wonder if there is something of importance here of spiritual formation. The love for what is true, what is beautiful, what is merciful and just, what is good and hopeful - and for the practice of love itself - must be a matter of the reformation of the spirit.

Since the heart is connected in one person to the mind and body, there is an indirect route through those parts. Discourse that immediately engages the thinking of a person may have a deeper resonance into the heart. The actions of the body which can be disciplined may have repercussions to the spirit. But the hardest part to reach, is the most important to be shaped.

We know that out of the heart a person speaks, meaning that both the thoughts of the mind and actions of the body are directed by a person's spirit. Emotions too are reflections of one's heart. The essence of spiritual formation is focused on the transformation of the human spirit by God's Spirit -with consequences for every other part of a human being.

I wonder if the arts are a way of speaking more directly to the heart. Moving music, an engaging story, a well-directed film, evocative paintings, poetry, and many other 'arts' seem in my experience to get into a person's heart, or spirit . . . pushing beyond the mind's thoughts and body's actions.

Not every use of the arts speaks to every person's spirit, but I wonder if there is something of importance here of spiritual formation. The love for what is true, what is beautiful, what is merciful and just, what is good and hopeful - and for the practice of love itself - must be a matter of the reformation of the spirit.

Wednesday, February 16, 2005

The Problem with Metaphors

I am quoting someone (but forgot long ago who said it) when I say "all analogies limp." It's true. Analogies are illustrations to help us understand something, but all are imperfect and if pushed too far or taken in the wrong way they can really cause problems.

Over the last couple of years I have heard the question asked "are our churches are more like cruise ships or battleships?" In other words, are Christians looking for fun, relaxation, and pleasure while the church staff labors to keep them happy, or are we all serving selflessly a greater good? Do we whine if something isn't to our liking, or are we prepared to endure hardship because my personal comfort-level isn't what is paramount.

You get the picture . . . and in some ways this image isn't too bad. But there is a part of me of cringes anytime Christians start using militaristic analogies. I know there is biblical precedent, but my point is that there is a great danger of being misunderstood - by either those who are believers or those who aren't.

To someone leery of Christianity "battleship-talk" and the language of "spiritual warfare" fits all too easily their perceptions that Christians long to rule over the world and subdue by force nonbelievers. Of course, that's what Muslims want to do, right? Not us! How could anyone think that about Christians? Well, just listen to us sometimes . . .

Perhaps a way to modify the analogy is to ask whether being a church together with others is like "being on a cruise ship or on a hospital ship?" We keep the contrast of "here to be served and made happy" versus "here to serve unselfishly" without appearing like crusaders.

Over the last couple of years I have heard the question asked "are our churches are more like cruise ships or battleships?" In other words, are Christians looking for fun, relaxation, and pleasure while the church staff labors to keep them happy, or are we all serving selflessly a greater good? Do we whine if something isn't to our liking, or are we prepared to endure hardship because my personal comfort-level isn't what is paramount.

You get the picture . . . and in some ways this image isn't too bad. But there is a part of me of cringes anytime Christians start using militaristic analogies. I know there is biblical precedent, but my point is that there is a great danger of being misunderstood - by either those who are believers or those who aren't.

To someone leery of Christianity "battleship-talk" and the language of "spiritual warfare" fits all too easily their perceptions that Christians long to rule over the world and subdue by force nonbelievers. Of course, that's what Muslims want to do, right? Not us! How could anyone think that about Christians? Well, just listen to us sometimes . . .

Perhaps a way to modify the analogy is to ask whether being a church together with others is like "being on a cruise ship or on a hospital ship?" We keep the contrast of "here to be served and made happy" versus "here to serve unselfishly" without appearing like crusaders.

Wednesday, February 09, 2005

Ash Wednesday

Today is the beginning of Lent. For me this means no morning coffee.

I didn't choose to give up coffee because it will be some great sacrifice, but because it is part of my routine. Last year I chose to give up something I like, but not something I do regularly - which was missing the point. I wasn't connecting Lent with prayer, but seeing it more as some sort of duty.

I believe there is a profound difference between obedience and discipline, though both are important. Obedience does what is right, and discipline does what leads to spiritual formation. Last year I think my observance of Lent was more an obedience than a discipline.

By giving up coffee I am carving out a regular time that I will fill with prayer. The beverage is irrelevant, the discipline is the focus. That time each morning will be devoted to prayer and repentance.

I didn't choose to give up coffee because it will be some great sacrifice, but because it is part of my routine. Last year I chose to give up something I like, but not something I do regularly - which was missing the point. I wasn't connecting Lent with prayer, but seeing it more as some sort of duty.

I believe there is a profound difference between obedience and discipline, though both are important. Obedience does what is right, and discipline does what leads to spiritual formation. Last year I think my observance of Lent was more an obedience than a discipline.

By giving up coffee I am carving out a regular time that I will fill with prayer. The beverage is irrelevant, the discipline is the focus. That time each morning will be devoted to prayer and repentance.

Friday, February 04, 2005

Scripture as a Relational Moment

Before the invention of the printing press the reading of scripture was a relational event, something heard aloud in the company of others rather than an individual activity one experienced within oneself. We could even back up further to the oral tradition that preceded much of scripture - even more relational.

Today we carry scripture around in books, on PDA's, access it on our computers, and have the opportunity to bring ourselves to scripture constantly. Of tremendous importance is the mindset I bring to that encounter with holy writing.

I've heard many metaphors which compare the Bible to some other type of printed material: it is a blueprint, the constitution of the church, an owner's manual for human beings, the book containing all the answers (like a dictionary or encyclopedia), a road map, or something else. All of these suggest a mentality one should bring to an encounter with scripture. Come looking for a pattern or bylaws to govern things, bring your questions about life, ask your questions about anything, find out how to get where you are going, etc.

There are other metaphors that I've not personally heard people use, but they use the Bible in other ways. One is as a business model. A really bad one is that Bible is a treasure map with clues to wealth and success.

I will concede that none of these metaphors is totally without some truthful aspect, but some only have a sliver of redeeming application and in general are quite misleading. Each metaphor suggests the intention of scripture, and therefore the mindset I should bring to reading scripture.

One deficiency I see with all these comparisons is that they emphasize that the Bible is a resource of information. Our interaction with scripture is therefore primarily intellectual.

Since scripture is written, it would be easy to think like this. But if we take seriously the Hebrew writer's statement that the Word of God is living and active (4:12), and believe that scripture is the Word of God, then in a mysterious way the person of God is encountered through scripture. And so I believe that some relational metaphors, instead of informational ones, might be better to set my mind in the proper frame.

As far as the people whose stories are found in the Bible I think about the possibility of approaching them as I would a family reunion. If your family is like mine, not everyone you see at the reunion is who you'd choose if it was a 'friends' reunion. Some might seem downright strange, to my way of looking at things. Reunions are where the family history is revisited in many ways, often the good and the bad. There is information, but only in the context of relational interaction - people with people. That is different than a person with a document: a person and a blueprint.

Undoubtedly wisdom, family history, and a perspective of one's own narrative would be informational benefits of the experience. Though the metaphor is hardly sufficient, I think there may be some benefit in orienting myself in this way rather than as if I am about to read a roadmap or constitution. I am about to enter a living conversation.

When it comes to encountering God, I think the relational becomes even more pronounced. For me scripture then becomes a 'place' where I interact with God. Rather than being God's instructional manual for me (almost suggesting God has left that in place of His personal presence), scripture is more like a coffee shop - a venue for dialogue. Though the words within the books of holy scripture don't change, they are the place where God speaks and so become a meeting place of creature and Creator where new things happen (certainly not the only meeting place, by any means).

Is there something helpful about opening your Bible with the expectation of entering an ongoing conversation rather than intending to search for and extract information? What happens when we change the expectations we bring to reading our Bibles?

Today we carry scripture around in books, on PDA's, access it on our computers, and have the opportunity to bring ourselves to scripture constantly. Of tremendous importance is the mindset I bring to that encounter with holy writing.

I've heard many metaphors which compare the Bible to some other type of printed material: it is a blueprint, the constitution of the church, an owner's manual for human beings, the book containing all the answers (like a dictionary or encyclopedia), a road map, or something else. All of these suggest a mentality one should bring to an encounter with scripture. Come looking for a pattern or bylaws to govern things, bring your questions about life, ask your questions about anything, find out how to get where you are going, etc.

There are other metaphors that I've not personally heard people use, but they use the Bible in other ways. One is as a business model. A really bad one is that Bible is a treasure map with clues to wealth and success.

I will concede that none of these metaphors is totally without some truthful aspect, but some only have a sliver of redeeming application and in general are quite misleading. Each metaphor suggests the intention of scripture, and therefore the mindset I should bring to reading scripture.

One deficiency I see with all these comparisons is that they emphasize that the Bible is a resource of information. Our interaction with scripture is therefore primarily intellectual.

Since scripture is written, it would be easy to think like this. But if we take seriously the Hebrew writer's statement that the Word of God is living and active (4:12), and believe that scripture is the Word of God, then in a mysterious way the person of God is encountered through scripture. And so I believe that some relational metaphors, instead of informational ones, might be better to set my mind in the proper frame.

As far as the people whose stories are found in the Bible I think about the possibility of approaching them as I would a family reunion. If your family is like mine, not everyone you see at the reunion is who you'd choose if it was a 'friends' reunion. Some might seem downright strange, to my way of looking at things. Reunions are where the family history is revisited in many ways, often the good and the bad. There is information, but only in the context of relational interaction - people with people. That is different than a person with a document: a person and a blueprint.

Undoubtedly wisdom, family history, and a perspective of one's own narrative would be informational benefits of the experience. Though the metaphor is hardly sufficient, I think there may be some benefit in orienting myself in this way rather than as if I am about to read a roadmap or constitution. I am about to enter a living conversation.

When it comes to encountering God, I think the relational becomes even more pronounced. For me scripture then becomes a 'place' where I interact with God. Rather than being God's instructional manual for me (almost suggesting God has left that in place of His personal presence), scripture is more like a coffee shop - a venue for dialogue. Though the words within the books of holy scripture don't change, they are the place where God speaks and so become a meeting place of creature and Creator where new things happen (certainly not the only meeting place, by any means).

Is there something helpful about opening your Bible with the expectation of entering an ongoing conversation rather than intending to search for and extract information? What happens when we change the expectations we bring to reading our Bibles?

Tuesday, February 01, 2005

Room for the Right Brain

I grew up in a Christian tradition that was very left-brained and so was all about thinking. Out of a desire to avoid being ostentatious, everything about our meeting places was minimalist and plain. Any sort of art was purely functional - like the flannel graph figures or pictures used to teach children Bible stories.

There is certainly an academic part of me that can be rational - but there has always been a creative part of me as well. In other words, I had a 'right-brain' side too. In fact, for a while I dreamed of becoming a commercial artist/illustrator - but that was discouraged by more practically-minded people (well-intentioned, I'm sure).

Now I am sharing in a community of believers that has room for the right brain - which is rediscovering art, beauty, creativity, and poetry . . . for at least me and I think for others as well. I am reading Brian McLaren's Generous Orthodoxy and one point he makes is that poetry is more capable than prose when it comes to talking about God.

Now I don't want to set up a fictitious conflict between the two sides of our brains, but rather to point out that prose has its place while I agree that it is incapable alone to express faith. I am finding that I am more of a mystic than a systematic theologian - though systematic theologians have blessed me in many ways throughout my journey.

Within our community of faith we have made a place for artistic expression - without labelling such work 'graven images' . . . because the point was not in the making of things but in the worshiping the works of our hands. That is a whole other subject - and we have worshiped our work plenty, though its not been the artistic work of our hands.

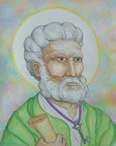

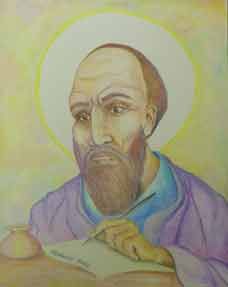

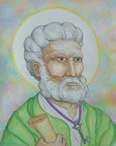

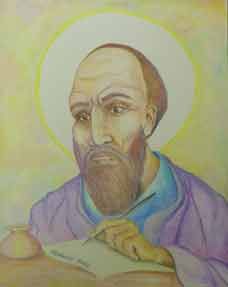

In finding a new place for my creative side I have created a couple of icons of Peter and Paul which are reminiscent of Eastern Orthodox icons.

I contribute these to our community not as decorative art, but symbolic art. In the style we affirm a connection with ancient Christianity, and in the depiction of Peter and Paul we are reminded of the spiritual unity of Jewish and Gentile Christians of the first century despite all their differences. May we be inspired to a similar unity.

There are many poets among us whose creative expression of faith will enrich the whole community.

There is certainly an academic part of me that can be rational - but there has always been a creative part of me as well. In other words, I had a 'right-brain' side too. In fact, for a while I dreamed of becoming a commercial artist/illustrator - but that was discouraged by more practically-minded people (well-intentioned, I'm sure).

Now I am sharing in a community of believers that has room for the right brain - which is rediscovering art, beauty, creativity, and poetry . . . for at least me and I think for others as well. I am reading Brian McLaren's Generous Orthodoxy and one point he makes is that poetry is more capable than prose when it comes to talking about God.

Now I don't want to set up a fictitious conflict between the two sides of our brains, but rather to point out that prose has its place while I agree that it is incapable alone to express faith. I am finding that I am more of a mystic than a systematic theologian - though systematic theologians have blessed me in many ways throughout my journey.

Within our community of faith we have made a place for artistic expression - without labelling such work 'graven images' . . . because the point was not in the making of things but in the worshiping the works of our hands. That is a whole other subject - and we have worshiped our work plenty, though its not been the artistic work of our hands.

In finding a new place for my creative side I have created a couple of icons of Peter and Paul which are reminiscent of Eastern Orthodox icons.

I contribute these to our community not as decorative art, but symbolic art. In the style we affirm a connection with ancient Christianity, and in the depiction of Peter and Paul we are reminded of the spiritual unity of Jewish and Gentile Christians of the first century despite all their differences. May we be inspired to a similar unity.

There are many poets among us whose creative expression of faith will enrich the whole community.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)